Let me start by saying this is a different kind of essay.

Silicon Valley fixates on the winners and polishes their origin stories. It forgets the startups that exploded on the launchpad and taught everyone how flight actually works. The failures rarely get written up, even though they often carry more signal.

K-Scale caught my attention for that reason. I’ve been tracking them for a while, and when they announced they were shutting down, I had to dive in to find out why. So I traced its journey.

This is the story of a team that built an open humanoid faster than companies with $675M behind them, and still ran out of runway. What they got right, and why they failed, tells us something uncomfortable about robots, capital, and openness in a market that does not naturally reward it.

K-scale’s ambition was to put a full-size humanoid in our living room for under $9,000 and make it all open-source. The kind of conviction that only comes from not knowing what you don't know.

"Accelerate the timeline to a world with billions of general-purpose robots, by making them open-source and universally accessible".

That was K-Scale’s mission.

The name came from the Kardashev scale, a framework Elon Musk often talks about. It was proposed in 1964 to measure a society's technological advancement by the amount of energy it consumes. Type 1 civilizations use their planet. Type 2 captures its star. Humanity still sits below type 1 by a wide margin.

The founders saw open-source humanoids as a stepping stone toward a Type 1 by distributing the gains of robotics early. Put simply, make the humanoid as open as Wikipedia.

Ben and the Garage

Ben Bolte (founder and CEO) did not start out trying to build humanoid robots. Before K-Scale, he had clawed his way into Meta FAIR after a month of hundred-hour weeks, then worked as an engineer on Tesla’s Full Self-Driving program. That résumé tells you two things: i) He knows how to squeeze learning out of messy data. ii) He refuses to ship black boxes he can’t open.

At one point, he tried a speech startup for call centers, but he woke up each morning not caring. He wanted to build things that walk, not things that talk.

By late 2023, he was unemployed in New York, auditing a Columbia robotics course and staring at the ceiling. A YouTube review of a cheap actuator went viral. He ordered a box from AliExpress and started experimenting. He applied to Y Combinator with a cofounder who later dropped out. YC accepted him solo.

At a hackathon soon after, Bolte met Matt Freidel, the only mechanical engineer he knew. He convinced Freidel to move to California and try to build a humanoid in three months.

Bolte wanted to compress Columbia’s walking robot course into a single 24-hour build using off-the-shelf actuators. Someone in the community challenged him. He pulled together a small group. Matt Freidel led hardware after time at General Dynamics Electric Boat and his own startup, Malamut. Paweł Budzianowski led software, bringing a Cambridge PhD in dialogue systems and prior ML lead experience at PolyAI.

They built a robot that could walk and dab.

That prototype became the first version of Z-Bot: a fully 3D-printable, open humanoid that cost only a few hundred dollars to build. It was small, crude, and limited. But it worked. More importantly, it spread.

Paweł Budzianowski (left) and Benjamin Bolte (right)

The Fork in the Road

In startups, investors often force you to skip evolution — go big faster. Bolte wanted to scale up this small, cheap bot (Z-Bot) to fund the big one. But a VC told Bolte to skip the toy and sell the dream. "Get 100 orders for the big K-Bot," the VC said, "and you'll raise $20 million easily.”

It was a beautiful thesis.

Bolte took the advice. He bet the company on it.

Why Humanoids at All

At its core, a humanoid is a mobile robot shaped to move through spaces built for human bodies.

Wait… aren’t 8 arms better than 2 arms + 2 legs?

Not really.

We don’t choose the human biped form out of vanity. We choose it because it makes sense. Civilization represents a multi-trillion-dollar capital investment optimized for bipeds. A humanoid fits where we already live. Door handles, shelves, tools, forklifts, scanners, all assume arms, legs, and reach like ours.

The usefulness of a humanoid is its generality. It pays for itself by switching tasks that no specialized robot could. A humanoid will be able to perform the long tail of physical work. Homes, offices, shops, warehouses, and kitchens are full of five-minute jobs with odd tools in odd places.

That choice comes with pain, however. Humanoids are hard. You can think of a humanoid working as three stacked layers working together.

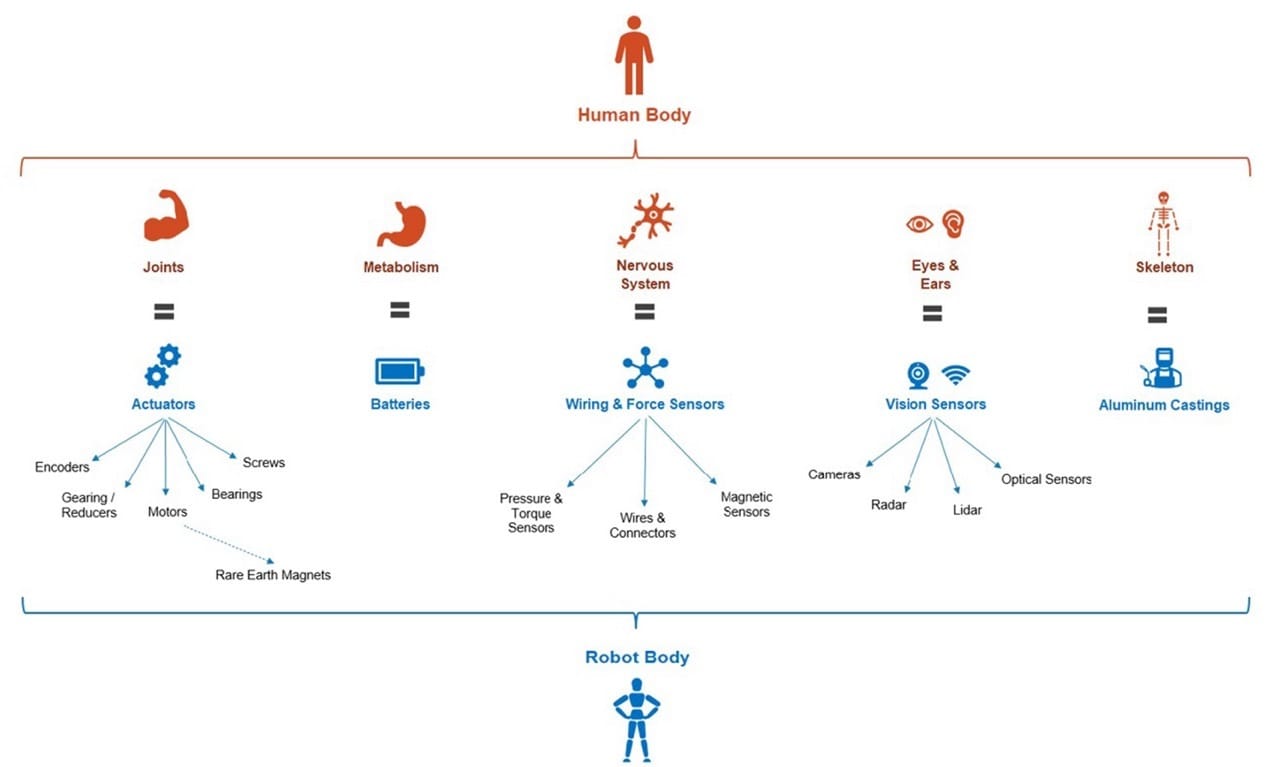

The Brain: An AI system that understands scenes and plans tasks.

The Nervous System: A motion controller handling balance and reflexes.

The Body: A skeleton packed with sensors, actuators, and batteries.

Mapping of Human Anatomy to Robot Parts

Anatomically, a humanoid robot is defined by degrees of freedom (DoF) or its independent axes of movement. A typical humanoid today has 20 or more DoF which allow human-like range of motion – meaning 20+ independent joints.

For comparison, an industrial arm might have 6 DoF. Having more DoF means more flexibility, but also more complex to control. Every extra joint creates an exponential expansion of possible physical states - a mathematical trap known as the curse of dimensionality.

This complexity is why humanoids have been “ten years away” for the last 50 years.

Recent advances in AI (especially vision and language understanding) and cheaper, better motors and sensors have finally brought humanoids to an inflection point. The slope finally points the right way.

Many occupations could be completed by humanoid robots

And the market for humanoids is huge. In our Machine Economy Thesis, we said:

Robotics is the next new multi-trillion-dollar market hiding in plain sight. It's the highest-upside, most underpriced leg of the AI trade. Labor is becoming more expensive and less available. This is a structural, not cyclical trend.

Roughly 76 million jobs may be automated by software and AI, but another 53 million hands-on roles like food prep, cleaning, and basic care require physical bodies. That is the humanoid wedge. Amazon already talks openly about replacing hundreds of thousands of roles with robots. Elon Musk claims AI and robots will replace all jobs. Hyperbole aside, the direction is clear.

Humanoids target the largest market imaginable: human labor itself, a $30 trillion global pool.

Morgan Stanley’s projects that if humanoids mature, we could see tens of millions of them in service by 2040, and over 63 million by 2050, contributing $3 trillion in economic value by taking on work across countless sectors.

High-pressure regions are likely to lead, while low-pressure markets lag.

The physics economics are undeniable. For the price of 1 kWh of electricity (~$0.25), a humanoid can deliver physical labor that would cost $20+ in human wages.

Pricing that runs downhill

Humanoids price in the opposite direction to yachts. Yachts get more expensive as you chase marginal gains in comfort and polish.

Humanoid robots will get cheaper as they get more capable.

How? Intelligence substitutes for hardware, learning replaces precision, and economies of scale compound design gains.

Right now, most humanoids are still in alpha or beta phases. There is a real autonomy gap to overcome. According to Bain, most humanoids still depend heavily on human input or remote supervision for complex tasks. They can move, lift, and demo well, but they are not yet independent workers.

China’s Unitree announced a G1 model at around $16,000. They recently also launched new Unitree H2 but their price is not yet public.

Tesla continues to frame Optimus as a general-purpose worker with a 20 kg payload and a long-term target price around $30,000. Figure takes a similar path, deploying robots in BMW plants. Its latest Figure 03 can fold laundry or load dishwashers. Analysts expect sub-$20,000 costs once production scales. Other closed players include Apptronik’s Apollo at ~$50,000. All of these are kept behind pilot programs or enterprise deals, not accessible to individual buyers.

1X recently introduced Neo, a home-focused humanoid now on preorder at $20,000 or a $499 monthly plan. During the initial 2026 rollout, Neo units in homes will be guided by human teleoperators to gather training data for Neo. This brings up some privacy questions since it involves remote operators and cameras watching users' homes.

Looking further out, Bank of America estimates that core humanoid hardware costs could fall to $13,000-$17,000 by 2035.

At the other end of the spectrum, new entrants are experimenting with radical cost compression. NOETIX Robotics’s Bumi is priced at only $1,375 and targets education and home learning rather than heavy labor. It achieves that price by using lightweight composite materials, a self-developed domain controller, and a highly localized supply chain.

Tesla Optimus Gen2 bill of materials (component-wise) as of Spring 2025. Source: OLLI Spring 2025

The pattern is clear. Capability is rising, prices are falling, and the biggest gains come from smarter software and tighter design loops.

How K-Scale Built K-Bot

Bolte rented a house in Atherton, stacked a small team into bunk rooms, and set a single constraint: build an open-source humanoid that developers could actually buy, poke at, and modify end to end.

Bolte was explicit about why he aimed at homes instead of factories. Learning needs messy environments. And trust in robots only comes when people can see what is running inside their house, and help improve it.

That belief sharpened as life did. Bolte became a father while building the company. His wife, a neurosurgeon, was working hundred-hour weeks through pregnancy. That kind of clock forces clarity.

The first robot, Stompy, was built a few blocks from their house in a rented garage. Fully 3D-printed. Assembled in under two months. Bolte spent about $20,000 out of pocket, with a bill of materials under $10,000 sourced largely from Amazon. It was scrappy and unstable, but it walked. More importantly, it proved a humanoid did not need a six-figure price tag to exist.

Y Combinator funding moved the team out of the garage. Bolte toured Chinese humanoid factory factories like Unitree and AGI Bot, studying how costs actually scale, then set a deliberately modest goal: sell 100 units in the US, then open the design so local manufacturers could build alongside them.

When they published the 3D-printed design, suppliers and engineers started reaching out with better parts and feedback. The feedback loop tightened. The robot got simpler, cheaper, and more manufacturable.

Then luck intervened. A Chinese company opening a Texas plant offered assembly space in a former Dallas newspaper printing facility. They already built golf carts and hoverboards, so the tooling, quality systems, and supplier networks across Vietnam and Thailand transferred cleanly and helped hedge tariff risk.

Across six generations in under a year, K-Scale moved from a garage prototype to a developer-ready humanoid priced around $11,000. That’s K-Bot.

K-Bot

K-Bot is a full-size humanoid, about 4 feet 7 inches tall.

(Watch this video, it’s inspiring)

The skeleton is made of 6061 aluminium, the same alloy used in bicycle frames and MacBooks. It has a clamshell design for its limbs, which protects the robot from bumps and falls and helps organize the internal wiring.

The head is intentionally modular, so owners can swap compute or add sensors such as stereo or depth without surgery. The robot's "hands" can also be easily swapped out for different tasks.

K-Bot uses quasi-direct drive (QDD) actuators, which is a mouthful meaning the gear ratio is low (10:1) enough that the motor can change direction quickly with less energy. This is vital for movements such as walking, where constant changes in direction happen. Traditional robots often used very high gear reductions (like 100:1), which multiply torque but make the joint stiff and prone to damage if it collides with something.

The robot's hip joint is a three-degree-of-freedom joint (side-to-side, front-to-back, and rotation). Most robots put the side-to-side joint before the forward-back joint. K-Bot uses the opposite order, which keeps the torso flat. And that allows K-Bot to sit in a chair or lie flat on its back, which is important for real-world use.

At the same time, the ankle uses a special system of bars so the motor's twisting force is exactly equal at the foot joint. This direct connection makes it much easier to create an accurate computer simulation of the robot's movements for testing.

You can also teleoperate the arms with a VR setup, move your own hands, and click to open or close the gripper. This makes it easy to collect demonstrations or do one-off tasks while your learned policies mature.

Regarding software, at its foundation is K-OS (K-Scale Operating System) that acts as the middleman between commands and the motor controls.

The Economics of Robots

K-Scale hit a price point most analysts did not expect the broader humanoid market to reach until the 2030s. A full-size robot at roughly $11,000 fundamentally changes who gets to participate. The personal computer only became a mass platform once prices dropped below $5,000. K-Scale was deliberately aiming for that kind of threshold.

On a normalized basis, K-Bot stood apart. Measured by value per mass, it came in at roughly $265 per kilogram. That is materially cheaper than closed competitors. Tesla’s aspirational $30,000 Optimus, for example, would land closer to $500+ per kilogram for a 57 kg robot.

This was the flywheel they believed in:

Lower entry price ➜ widens the builder base ➜ more data ➜ which tightens models ➜ which lowers hardware spec needed for the next run.

Could that price sustain a business? In practice, no.

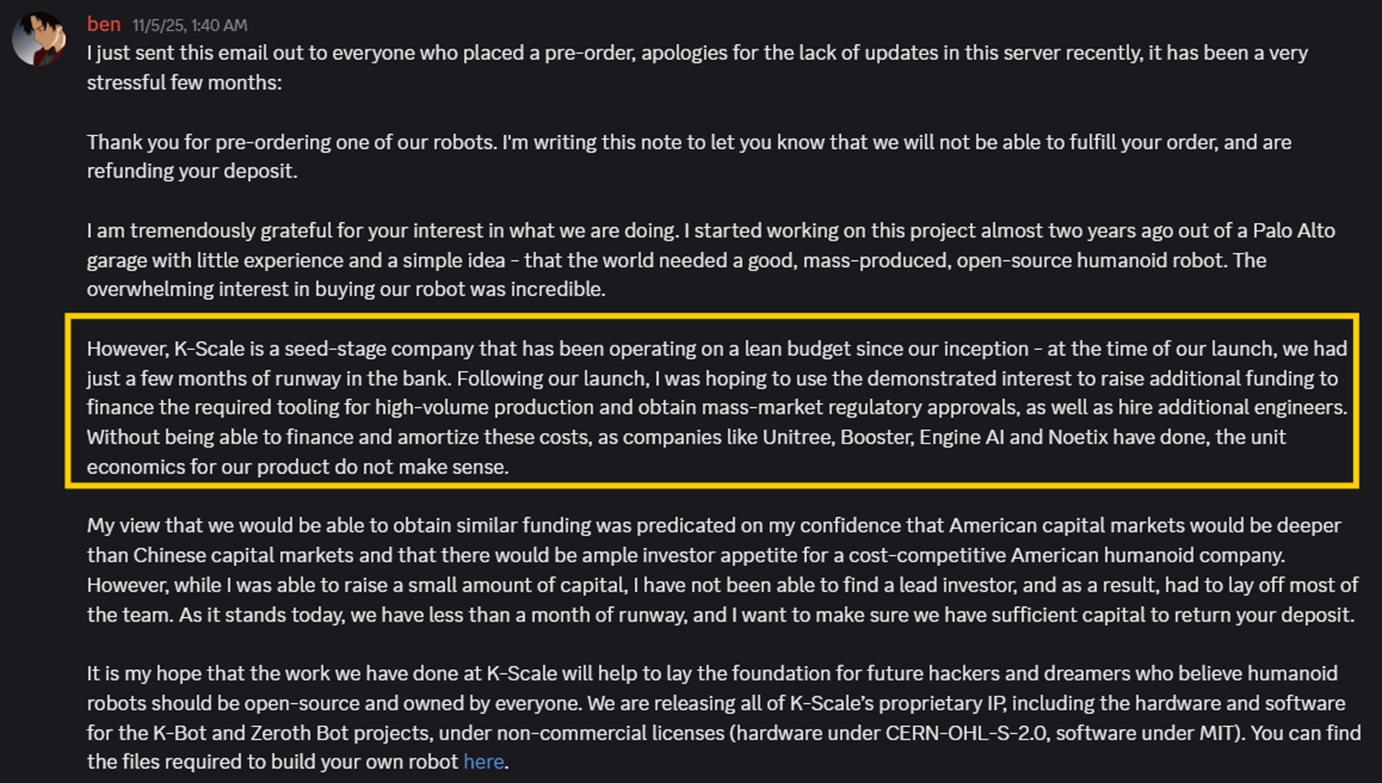

During its R&D-heavy pre-commercial phase, K-Scale burned about $164,000 per month. Total cash outflows reached $3+ million, compared with $1.3 million in inflows. It’s actually tiny compared to the big boys.

The plan was to make hardware close to break-even and earn profits on software and upgrades. Subscriptions were to be priced around $200 per month, with a roughly 94% gross margin. Aftermarket parts like compute modules and five-finger hands carried estimated margins between 40% and 62%.

They proved the price was technically possible. They did not prove it was financially survivable.

Orders, Names, and a Runway

Demand caught the team off guard. Within a year, K-Scale crossed $1 million in orders.

Customers could buy a base K-Bot or opt into a full autonomy package that promised free software and hardware upgrades until the robot became a fully autonomous household helper. Most early buyers chose the upgrade and agreed to share data and feedback. Bolte set a blunt target: three years to autonomy, or bankruptcy trying.

The buyer list looked strong. Former GitHub CEO Nat Friedman, MongoDB co-founder Eliot Horowitz, Mixpanel co-founder Suhail Doshi, the founder of SurveyMonkey, and an Apple VP who led the Apple Watch team.

Although no public valuation figures are disclosed for any of the rounds, they raised more than $1M from investors like Y Combinator, GFT Ventures, Lombard Street Ventures, Pioneer Fund, Unpopular Ventures.

They got as far as they did the old way: by keeping costs brutally low, living together, publishing their work, sleeping next to their robots, and developing muscle memory for catching them before they hit the floor.

Then the fundraising stalled.

On November 4, Ben sent the shocking update. Without a lead investor, the company would shut down.

He bet that US investors would support a cost-competitive American humanoid. But VCs looked at the hardware margins, shrugged, and went back to funding vertical AI startups.

If you have zero revenue, you have infinite potential. As soon as you ship a product and show some sales, the market prices you off those sales rather than the dream. K-Scale fell into the trap.

The team drove down the cost of a full-size humanoid through aggressive engineering and a clever supply-chain hack. They sourced from Chinese golf cart factories by telling them they were building luxury mobility devices. It worked.

But ultimately, this is a story about capital psychology.

Investors will wire hundreds of millions into closed humanoid companies at sky-high valuations, yet hesitate when a team says they’re going to make it cheaper and open-source.

You can see the math running in their heads. Closed robots promise moats and margins. Open robots have uncertain market capture, and raise uncomfortable questions about who owns the upside when the robot is basically a public good you can download from GitHub.

Five Lessons from K-Scale

As I ran through their story, I sat down to think about what might have changed the outcome. Boy, I would have loved to have a cheap, useful robot in my home today. A few lessons stood out, for founders and investors looking at the same problem.

#1 Revenue can be a liability at the wrong moment.

K-Scale pushed to secure 100 orders to prove demand. But instead of unlocking a Series A, their $1M in low-margin hardware revenue likely anchored investor expectations to hardware economics. As an investor, I can understand the psyche. Pre-revenue companies are priced on imagination. Post-revenue hardware companies are priced on sales and margins, and those were never going to look good early.

#2 Ignoring the small product was a strategic mistake (maybe)

The tiny Z-Bot had viral traction, cost roughly $300 to build, was easy to ship, and faced fewer regulatory hurdles. A slower path, but it could have funded iteration and community growth. The decision to abandon it was driven by fear of being labeled a “toy company” rather than by market pull.

To be fair, there is no guarantee Z-Bot would have generated meaningful cash flow. It might have distracted the team from the larger ambition. But it was a fork in the road.

#3 Supply chains are vital.

Chinese robotics companies iterate faster because design, suppliers, assembly, and feedback loops sit in the same place. They can ship something that fails, learn from it, and reship before a US team finishes a single prototype revision.

This is why I think the US faces a real uphill battle with China in robotics. China has spent decades building manufacturing depth, and that investment is now compounding across EVs, drones, and robots.

Software crowned the US. Silicon Valley won by concentrating the world’s best digital talent. Robotics is a different arena. If robots become a thing (I believe they will), the balance of power could shift meaningfully over the next 5 to 10 years.

Even when manufacturing is outsourced, tight integration is what separates durable platforms from commodity hardware. DJI’s advantage in drones came from that integration, not simply from making things in China.

#4 The humanoid market risks breaking in two bad ways

Ben’s “Hoverboard versus DJI” framing in his investor whitepaper captures it well. Early consolidation (like in consumer drones) can kill openness and experimentation. Whereas unchecked commoditization (e.g., hoverboards) can undermine quality and safety. The market has to thread a narrow path between the two.

Prices will fall. Hardware markets almost always push that way. It means that teams that ship functional robots at aggressively low price points will undercut premium-first strategies. Over time, hardware margins will look more like those of consumer electronics. The real businesses will be built on high-margin layers like upgrades, spare parts, and recurring software.

#5 Open source is a long-term advantage, not a go-to-market strategy

K-Scale tried to be the open platform before a closed, category-defining humanoid had established our expectations. Historically, open platforms (e.g. Android vs iOS) tend to scale after a category has:

a stable form factor

clear performance expectations

an economic model people trust

Open hardware may win over decades, but the market may first require a closed winner (perhaps Tesla or Figure) to set norms around capability, safety, and pricing.

Early adoption of open systems must be developer-led. A strong developer ecosystem creates the feedback loops and network effects that eventually make openness durable.

The Body Is Free

There is a good ending to this story.

When hardware startups die, their work usually vanishes with them. The IP gets locked on a server, auctioned off, or absorbed by a larger company and buried. What was learned becomes inaccessible, and whatever progress was made effectively resets.

K-Scale chose not to do that.

Instead of closing the doors, they blew them off the hinges. They opened everything - the hardware schematics, the software stack, the proprietary IP - all of it is now open-source under non-commercial licenses. What survives is the ability to tinker without permission, the adversarial interoperability that made the early internet powerful.

K-Scale showed that a small, scrappy team with an open-source ethos can build something genuinely extraordinary out of a garage. I have deep respect for Ben and the team who worked relentlessly for their vision.

That’s what continues to fascinate me about tech. Even when a company fails, the future does not have to. Others will build on it, copy it, cheapen it, and improve it. That is the part that compounds.

Cheers,

Teng Yan and Ravi

References

This interview with Ben was invaluable in reconstructing the sequence of events and the team’s internal decisions.

The K-Scale investor whitepaper was a gem and laid out the team’s thinking and technical approach in clear detail.

And if you enjoyed this, you’ll like the rest of what we do:

Chainofthought.xyz: Decentralized AI + Robotics newsletter & deep dives

Our Decentralized AI canon 2025: Our open library of industry reports

Prefer watching? Tune in on YouTube. You can also find me on X and LinkedIN