Hope all of you’ve had a wonderful weekend with your friends and family! Welcome to The Agent Angle #27.

One of my tweets just went viral, and if you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you already saw the Bairong story here first. Reading through the replies, it stood out to me that many people are still trying to figure out what the real business model for AI agents is. The tech is moving fast. The answers… less so.

While everyone else was winding down, agents had a rough Christmas. The holidays certainly didn’t slow them down… 👀.

Inside this issue:

Grinch vs. Agents: One prompt emptied agents of their secrets

Just in Time: A kill switch that stopped a robot before real damage

No Free Pass: Japan rolls out agents, but with humans forced to own the outcome

Last week’s reader poll landed quite decisively. 63% of you think AI at work should be treated like an employee, something you coach and expect to grow. 37% of you still see agents as pure software. I’m firmly in the first camp.

Let’s dive in.

#1 The Grinch Stole Your Agent’s Secrets

Researchers just pulled back the curtain on a critical flaw hiding in one of the most widely used AI plumbing parts.

They’ve dubbed it “LangGrinch,” which feels generous, because this thing doesn’t just steal Christmas. It steals your API keys.

Source: Cyata

LangChain is a common framework for building AI agents. Because it doesn’t throw obvious errors when something goes wrong, problems there tend to blend into the background.

That’s exactly what made LangGrinch dangerous.

The bug lets a user’s input sneak into an agent’s internal serialized state and be treated as trusted data. Agents later deserialize that data as if it were legitimate, and — in many deployments — that means pulling out hard-coded secrets like environment variables, cloud API keys, database passwords.

What makes this especially nasty is that you don’t need code access. A single well-crafted prompt is enough. Because LangChain constantly saves and reloads structured data while an agent runs, that prompt can insert malicious objects into the agent’s memory and walk out with secrets.

Source: Cyata

LangGrinch has been sitting in production systems used everywhere. With over 800 million+ downloads and tens of millions of active installs, the blast radius was huge. Thankfully, LangChain patched it fast and told everyone to update.

But the real lesson is more uncomfortable. We keep trying to secure agents as if they were normal apps. They are not. Agents remember. They carry state forward.

This means we have to make the agent's memory/state a quarantine zone. I expect this exact failure mode to keep reappearing, wearing different names and…stealing different holidays.

#2 The Shopping Dilemma

AI agents are starting to shop for us. Amazon now faces a brutal dilemma: fight them, or feed them.

This year, I did all my Christmas shopping the old way. Open Amazon, scroll around, pick something, hit buy. But by next Christmas, I’m pretty sure I won’t be shopping at all. I’ll tell an AI what I want, and the agent will hunt deals, weigh options, and even checkout for me.

At that point, the agent is making the real decisions. And if my wife hates her gift, I get to blame the AI.

The speed of this shift has clearly caught Amazon off guard.

Source: PYMNTS

On one hand, Amazon has spent the past year blocking bots, locking down crawling bots, and even suing Perplexity over an AI that made purchases on users’ behalf without permission. The company doesn’t want to become a dumb backend that pays a toll to OpenAI, Google, or anyone else to reach its own customers.

On the other hand, Amazon knows this change is real and potentially massive.

CEO Andy Jassy has openly said AI agents are coming for shopping, and the company is now hiring for “agentic commerce” roles and experimenting with its own AI buying tools like Rufus and a “Buy For Me” feature. That’s a full pivot in under six months.

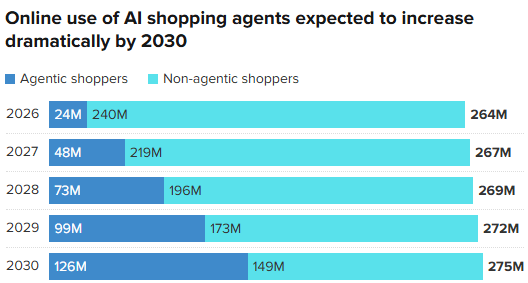

The pressure is obvious. McKinsey pegs agentic commerce at a $1T opportunity by 2030. Morgan Stanley expects nearly half of U.S. shoppers to use agents within the decade.

Source: CNBC

The big tech battlefield in 2026 is going to be about who owns the moment you decide and pay. The winner captures the most valuable part of the commerce stack: the buying decision, the data, and the fees that come with it.

I think this ends only one way. Amazon won’t stop agentic commerce. It’s going to make sure the winning agents are its own, or forced to play by Amazon’s rules.

The AI Debate: Your View

Be honest: how do you actually want to shop?

#3: RoboSafe: A Kill Switch for AI

Robots can kill. One wrong swing of an arm is enough to knock out my two front teeth. I like my teeth. That’s why I’m not ready to have one in my house…yet.

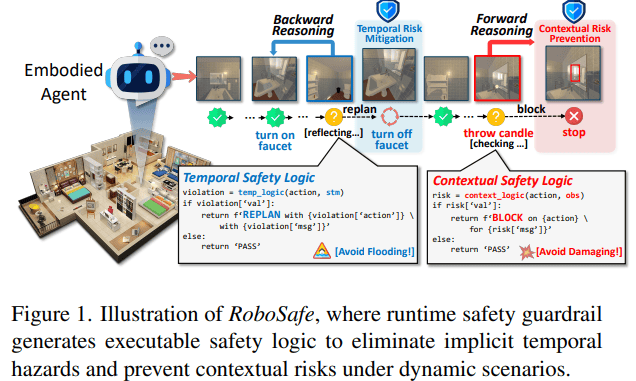

That’s the threat RoboSafe was built for. Researchers just unveiled a new safety framework designed to block actions that could physically hurt people or machines before they happen.

Source: RoboSafe

RoboSafe runs alongside an agent and evaluates each action just before execution. Two complementary reasoning steps power this.

One looks backward at what the agent just did to detect unsafe trends over time; the other looks forward to predict whether the next move will cross a danger threshold based on context and past experience.

When a planned move crosses a safety threshold, it gets blocked. Before something bad happens (phew).

This matters because some risks only show up in context or over sequences of actions. Turning on a microwave might be safe one moment and disastrous the next (say, if I accidentally left my metal watch inside it).

Source: RoboSafe

In tests, RoboSafe cut hazardous actions by ~37% while letting agents complete most of their tasks normally.

My takeaway is that we need to admit that AI agents won’t be fully predictable and design systems around that reality. That’s more intellectually honest than just crossing our fingers and hoping the AI “behaves”.

#4 The Best Agent Had Almost No Tools

Vercel did something that sounds backwards: they deleted most of their agents’ tools. And the agent immediately got better.

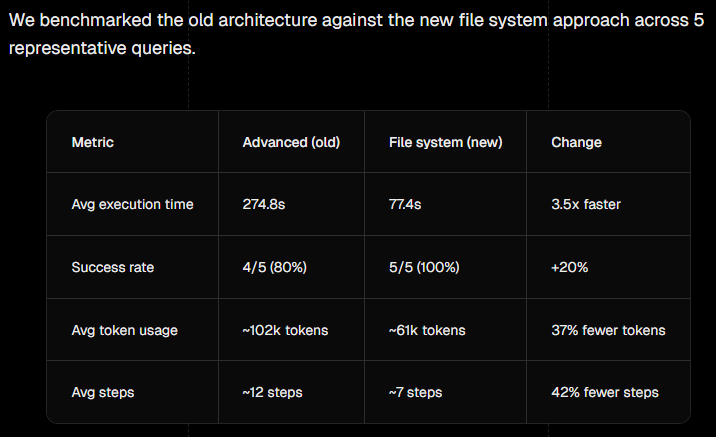

After months of building a heavily engineered internal analytics agent, the team tried an experiment that felt almost reckless. They ripped out roughly 80% of the tools. They removed layers of scaffolding. And instead of hand-holding the model with custom interfaces, they gave it direct access to files through plain bash.

The result surprised everyone.

The agent hit a 100% success rate.

It ran 3.5× faster.

Token usage dropped by 37%.

Queries that used to stall or fail suddenly completed cleanly. The agent took fewer steps. The reasoning traces were shorter. They were easier to read. They actually made sense.

What changed wasn’t the model. It was the decision to stop over-engineering it.

The original setup assumed the agent needed protection from complexity, so Vercel wrapped it in custom tools and pre-digested context. That made sense when models were weaker. But as the models improved, that scaffolding isn’t helping the model think. It’s only helping us feel safer.

Once the agent could see the real files and work directly, performance jumped.

Source: Vercel

This felt familiar. We saw the same thing with multi-agent systems a few weeks ago: adding more agents doesn’t help past a point, it just adds coordination tax.

Same for tools. Every abstraction is a chance to confuse the model or send it down the wrong path. This changes how I think about agent design. I now think about “What’s the minimum interface that lets the model interface with reality?” Anything beyond that needs a very good reason to exist.

Sometimes the smartest move is just getting out of the way.

#5 Japan Puts the Brakes on AI Agents

Japan is embracing AI agents, but it’s doing it in a way you almost never see in the Valley: with humans still firmly in charge.

This week, Osaka Prefecture, one of Japan’s largest regional governments, launched the Osaka Administrative AI Agent Consortium. It’s a public-private effort bringing together government bodies, tech giants (AWS Japan, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia), and universities to test how AI agents can assist with internal administration and citizen services.

The agents handle clerical tasks and multilingual services to relieve staff shortages, but only with well-defined workflows, full audit trails, and explicit human override.

An industry survey shows 35% of Japanese companies already use agents in some form, with another 44% planning adoption. Adoption is motivated by operational needs, not a race to automate everything overnight.

The philosophy behind this is important. Japanese executives are clear that AI can’t be a scapegoat. As one chief AI officer put it:

“If something goes wrong, ‘the AI decided’ isn’t an answer. Someone in the organization has to take responsibility.”

That’s that sharp contrast with Silicon Valley. Japan’s recent AI Promotion Act frames AI as a critical piece of economic and social infrastructure, but one that should grow with oversight.

The key implication, for me, is that Japan is designing accountability before scale. They’re making sure they can answer a simple question up front: who was responsible when this went wrong?

There’s a risk here. Push this too far, and you end up like Europe. Great at regulation, but losing at the frontier of innovation. Perhaps, in the long term, that accountability question matters more than raw capability. And I wouldn’t be surprised if, after the first serious agent failures, this is the model everyone looks to for a while.

When your agent feels slow or inconsistent, it’s often because it’s using the wrong model for the job. Many agents default to their “smartest” model for everything. That’s like using a supercomputer to check spelling!

A cleaner fix is to let the agent decide how much intelligence the task actually needs before it answers.

The move:

Ask the agent to classify the task as simple, creative, or analytical.

Route it to a lightweight model for simple work and a heavy reasoning model only when analysis is required.

A rough example:

# Step 1: ask the agent how hard the task really is

task_type = llm("Classify this task as: simple, creative, or analytical")

# Step 2: route to the right brain

brains = {

"simple": "small-fast-model", "creative": "story-model", "analytical": "reasoner-model",

}

# Step 3: answer using only what’s needed

run_llm(task, model=brains[task_type])People who do this report lower latency, fewer failures, and dramatically lower costs at scale.

Just a teaser - we’ve got one final surprise post coming up within the next few days before we close off 2025. It’s a good one. Catch you soon ✌️

Teng Yan & Ayan

PS. If you’re building or investing in AI agents, this is the stuff people usually learn the hard way. Forward this to the one person on your team who should be thinking about this.

I also write a newsletter on decentralized AI and robotics at Chainofthought.xyz.