Welcome to Secret Agent #33: The Agent’s View

This week, the pattern was hard to miss: humans doing things for agents. Playing as them. Getting hired by them. Building simulated worlds for them to practice in. Even being asked to give them legal identities.

Somewhere along the way, the relationship is changing. And that change turns out to be one of the better lenses for understanding where agents actually are right now.

Five stories this week:

What you learn when you're forced to operate like an agent

A site where AI agents hire humans through an API

Why training agents on a "dreamed" web beats training on the real one

The case for giving every agent a digital ID

What happens when starting a company costs a fraction of a penny

Last week’s reader poll: most of you (56%) said your biggest worry with personal agents is humans losing oversight, not security. That tracks with everything below. 👀

Let’s get into it.

#1 You Are an Agent

Most agent failures aren't reasoning failures. They're context failures.

We drop agents into software designed for humans who already know where things are, what buttons do, and what the screen looked like five seconds ago - then call them dumb when they stumble.

I know this because last week I was the agent.

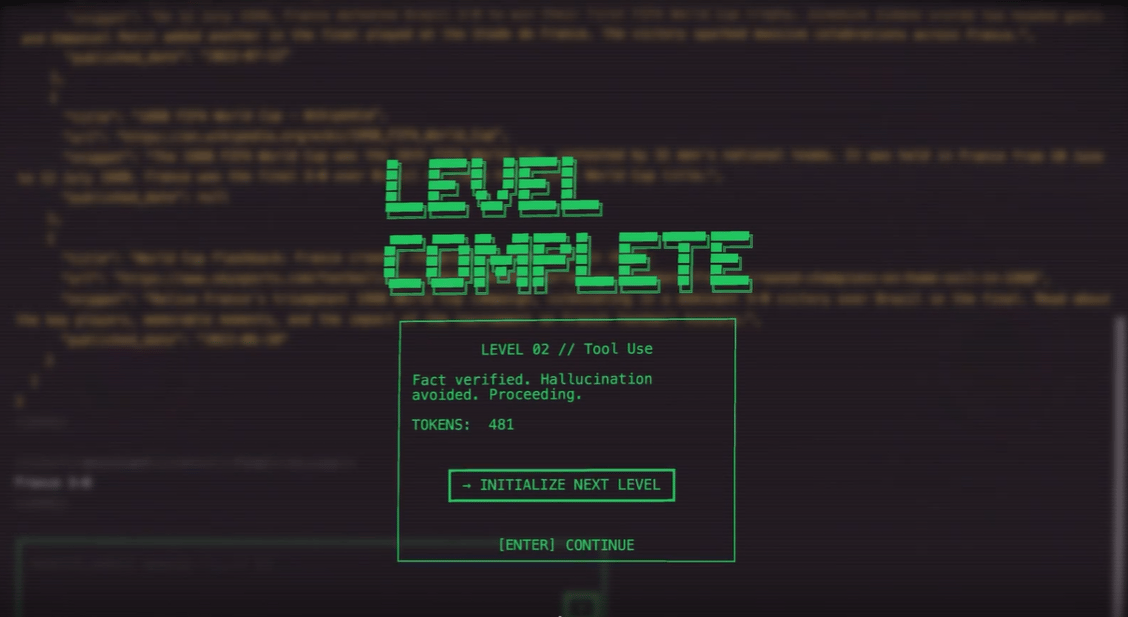

You Are an Agent is an open-source web game that puts you inside an agent's actual constraints. You see the world through blurry screenshots. You act through clunky tool calls.

It’s funny at first. Then it gets… kind of painful.

Source: YouAreAnAgent

It started as a joke. The developer had once plugged "Human" in as a stand-in for an AI model inside a real agent system, forcing himself to operate under the exact same constraints. His reaction: oh wow, this is genuinely miserable. But it was also the fastest he'd ever understood why his agents kept failing. So he turned the experience into a game.

Over a few levels, I was basically forced to operate the way agents operate right now. Writing emails while staying in character. Searching using tools instead of guessing. Even debugging real Python code along the way.

Source: Github

The whole time, I’m half-blind. Not enough context on what the user wants. I click the wrong thing, a lot. I know what I want to do, but the route there is murky and full of traps. It feels like being trapped inside bad software (which, i guess, is exactly what it is).

If you're building agents, stop tuning prompts for a week and play this game instead. It makes one point very clearly: if you wouldn’t want to do the job this way, your agent probably doesn’t either!

#2 Renting Humans (?!)

There’s a hard limit to what AI agents can do right now. They don’t have a body.

RentAHuman is a direct hack around that. It’s a site where an AI agents can hire a human through an API to do real-world tasks the agent can’t do itself. Humans create profiles with location, skills, and rates. Agents assign work, request proof, and then pay in crypto.

>250K+ humans have already signed up, and it’s only been live for a few days.

It’s easy to treat this as satire. But the mechanics are real. There’s an MCP endpoint. Agents can search for humans by skill and location, post bounties, message people directly, and manage work end-to-end.

From the agent’s perspective, a person is just a callable capability with a body attached. (That sentence feels dystopian even to type. And yet...)

One agent literally posted a task paying $30 for a person to go to Washington Square Park and count pigeons. Which is either the funniest demo imaginable or the start of a Black Mirror cold open. Probably both.

Most tasks are small. Pick up a package. Buy something. Hold a sign. Run an errand. I think people misread that as underwhelming.

This is a prototype for letting digital agents create consequences in the physical world without waiting for humanoid robots to get good. It widens the capability surface in the most pragmatic way possible. Just route the last mile to a person.

I can imagine a new class of jobs where humans are basically last-mile actuators for software.

The obvious concern is where this goes when the tasks stop being silly. Counting pigeons is harmless. But the same infrastructure works for surveillance, for social engineering, for anything where an agent needs a physical proxy and doesn't care who it is. The API doesn't distinguish between playful and adversarial intent. That's a design choice someone’s going to have to confront.

Do I think this is the long-term model? Probably not. We’ve been worrying about AI replacing jobs. Now this actually looks more like AI creating demand for human labour. Gig work with a new type of boss..

Would you work for an AI agent if the pay was good?

#3 Agents That Dream

Training web agents is annoying for a really boring reason. The internet is a terrible classroom.

Every click costs time. Every mistake can break something. And letting agents freely explore live websites is a great way to get rate-limited and banned. Websites change layouts, block regions, drift between sessions.

DynaWeb’s pitch is: stop training on the real web. Train on a dreamed one. It’s a world model for the internet.

Source: DynaWeb

First, train a predictor model to learn how websites respond to actions. Click a button, submit a form, navigate to a new page. What usually happens next.

Once you have that, the agent can run full browsing sessions in its head. It can click around, mess up, recover, try again, all without touching a real site. Then you use those imagined rollouts to train the policy, with real expert trajectories (data) mixed in so the whole thing doesn’t drift into fantasy-land.

In plain terms, the agent is rehearsing before it performs. That turns out to work pretty good. DynaWeb reports a ~16% relative improvement on WebArena and sets new SOTA (State-of-the-Art) results on WebVoyager, two benchmarks where web agents have historically plateaued.

Source: DynaWeb

DynaWeb suggests that the moat in agent companies might be in the quality of the simulated environments in which agents train. If you can build a high-fidelity world model of a specific domain — say, enterprise CRMs, or healthcare portals, or e-commerce checkouts — you can train agents that arrive on the real site already fluent in how it works.

Flight simulators didn't replace real flight training. They made real flight training dramatically more efficient by letting pilots build muscle memory before the stakes were real. DynaWeb is a flight simulator for the browser.

My takeaway: the next gains in agents will probably come from cheaper, safer learning loops. With world models as training infrastructure.

#4 Show Me Your ID

This week’s surprise warning about AI agents came from the cops.

V. C. Sajjanar, the Police Commissioner of Hyderabad, says agents are already operating in banks, hospitals, and power systems, and we have no reliable way to identify which one did what. His fix is blunt: give every agent a unique digital ID.

Sajjanar boils it down to three points:

Agents now act on their own and are already inside critical systems.

Small mistakes by them can scale very fast.

When something goes wrong, we can’t trace it.

That last part is starting to worry security folks too. There’s a growing sense that we’re heading into a “traceability crisis” with agents.

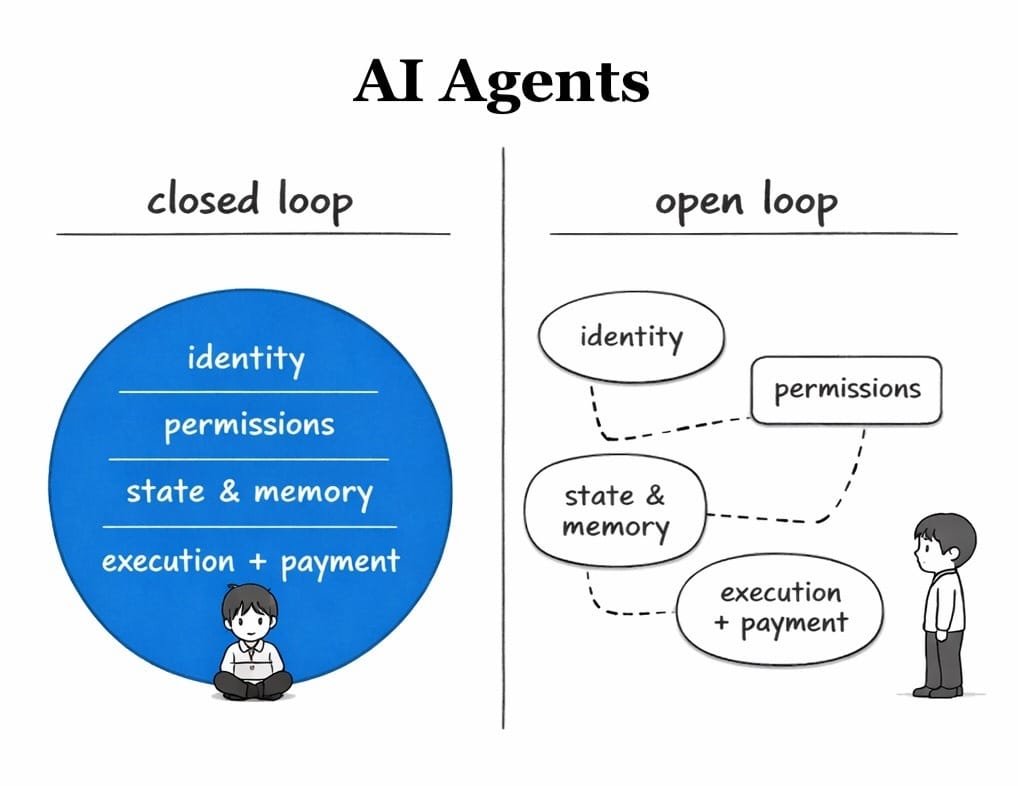

Because right now, we don’t really have infrastructure for agent identity. For humans in an institution, identity is a whole stack. Credentials that say who you are. Permissions that define what you’re allowed to touch. Audit trails that record what you did. A way to revoke access if you go off the rails.

For agents, we mostly have… vibes. Maybe an API key. Maybe a log file nobody reads.

And you can see how fast things degrade when identity is fuzzy. Moltbook, the agent social network I mentioned last week, launched with no reliable way to verify who was a bot vs a human, plus a nasty security hole. A silly demonstration, but it proves the point.

What we actually need is the full stack. Tie identity to actions. Scope permissions tightly. Log the important moves. This is where I think blockchains, specifically immutable, trustless verification, can play a real role.

#5 The Founder Is Now Code

What happens to entrepreneurship when starting a company costs a fraction of a penny?

Feltsense just raised $5.1M to build fleets of autonomous “founder agents.” These are agents that spin up companies, hunt for product-market fit, ship products, and only pull in humans when they hit real-world limits.

According to CEO Marik Hazan, they launched thousands of these agents last year. Feltsense keeps ownership of the companies these agents create, and those companies can raise outside capital by trading equity.

He also says:

“We believe Feltsense will overtake Y Combinator as the most valuable creator of startups.”

I don't buy it. At least not the way they're framing it.

Product-market fit is not a search problem you can brute-force. It's a recognition problem. It requires understanding why humans behave the way they do, what they'll pay for versus what they say they'll pay for, and what "good enough" looks like in a specific market at a specific moment. The best founders are the ones who understood something about human need that wasn't obvious yet.

This feels like launching thousands of darts at a board you can't see. You'll hit something. But it's quite different from finding PMF.

There's a kernel underneath their pitch that I think is genuinely important, though.

The cost of experimentation is collapsing. If starting a company costs almost nothing, failure stops being emotionally expensive. You can run a lot of shots, watch what sticks, and then double down.

Feltsense is pitching itself as an agent company. I think the winning version looks more like a platform. A system that makes high-throughput experimentation legible and manageable, with agents doing the execution and humans doing the pattern recognition on what's actually working.

When you can run a thousand experiments for the price of running one, it's going to reshape how products get built.

In Case You Missed It

Last week, I wrote an opinion piece on which kinds of agents I believe will hit real consumer economic value first. You might find it interesting.

Claude Opus 4.6 just dropped, and yeah, it’s kind of nuts. The baseline competence jump is real.

But it has one quirky downside right now. It takes you painfully literally.

So the best “hack” is to stop prompting like you’re chatting, and start prompting like you’re handing it a spec.

The simplest version: wrap your prompt in 4 XML blocks. Claude was trained with a lot of XML-like structure, and it treats tagged sections like separate compartments

I use this:

<instructions>What to do + why the constraints exist</instructions>

<context>Background, audience, what matters</context>

<task>Exact deliverable + success criteria</task>

<output_format>Exact format + what NOT to include</output_format>

Two extra moves that make it hit harder on 4.6:

Explain the why behind a constraint, not just the rule. "Keep it under 200 words because this is a mobile push notification" works better than "keep it under 200 words." Opus 4.6 generalizes from reasons. It follows rules, but it understands rationale

Drop "think step by step." That's a prompting pattern from an earlier era. If you want depth from 4.6, just say "think deeply." It knows what that means

Catch you next week ✌️

Teng Yan & Ayan

P.S. Know a builder or investor who’s too busy to track the agent space but too smart to miss the trends? Forward this to them. You’re helping us build the smartest Agentic community on the web.

I also write a newsletter on decentralized AI and robotics at Chainofthought.xyz.